Platform QA

Once individual development teams are made responsible for the quality of the work they deliver, the role of a dedicated quality assurance team needs to change. In some circumstances, it may not make sense to have a dedicated QA team at all, with testers simply joining separate agile development teams. This article describes an experience where quality was improved by an anti-parallel move: re-assembling a dedicated QA team with a rethought mandate of addressing platform risks. In implementing this, concepts taken from Large Scale Scrum (LeSS) and tools for Behaviour Driven Development (BDD) were key. We called this team structure Platform QA.

This approach to QA, and the name, was evolved as a team effort together with my brilliant former colleagues Arun Prasad Songappan Shanmugam and Srikanth Nallan.

What is a Platform QA Team?

A Platform QA Team is

- a dedicated, full-time, engineering team

- that identifies and reduces platform risks

- to improve the product provided by that platform

- in partnership with other development teams

So that this general definition is not too easily mistaken for traditional QA, it is important to note that the focus of the team is on QA engineers doing hands-on technical change across tests, tools and platform, as well as process coaching. Sign-off for particular component deliveries is explicitly out of scope. Other QA team structures and processes are contrasted later in this article.

Example tasks from a typical week are:

- Pairing with a developer who is setting up new performance testing tools with their component for the first time

- Design discussion on test approaches and coverage after an incident retrospective, and contributing some test case improvements and reviews accordingly

- Investigating why a particular continuous build test environment disk keeps filling up

- Doing exploratory testing to improve understanding of particular use cases or parts of the system

The idea of QA as a horizontal, working with multiple development teams, is not new. Such horizontals can tend to be very expansive, in keeping with an idea that testing skills are highly generalizable and fungible across large parts of the organization, like an audit or infrastructural function. A Platform QA team is more focused. It deals with only one product and one platform.

Product and Platform

Defining the product being worked on is a key organizational question, and we mean it in the same sense used by Large Scale Scrum (LeSS). Each definition will be organization specific, but a brief rule of thumb is: big enough that it directly serves a customer need, small enough that a single product owner can make informed final decisions. For us the product was Asia equities electronic trading. The platform is then everything that delivers that product. For software development organizations, and certainly for ours, that fits within the more general definition given by Benjamin Bratton:

A […] platform [is] a standards-based technical-economic system that simultaneously distributes interfaces through their remote coordination and centralizes their integrated control through that same coordination. – Benjamin Bratton, The Stack

These two definitions provide an important border for practical action by the Platform QA team. The product, and components within the platform, are the primary responsibility of the Platform QA team. Team members are expected to get their hands dirty learning and making changes in these components. This requires working closely with people in other teams working on the same product and platform. Other teams and components beyond this boundary are instead treated as matters of polite neighbourly concern.

Quality Risk Backlog

Our Platform QA team maintained and published a quality risk backlog which described current and planned tasks. Items for the backlog were refined from discussion on a regular two-weekly meeting between the QA team and representatives from other development teams, including periodic management attendance. This emerged as a forum where approaches that varied across teams could converge on common conventions and standards. Tool design and improvement was also a recurring theme. The decision of which tasks to take was made by the QA team itself and only rarely aligned with larger project or regulatory deadlines. This was by design: even well-intentioned involvement devolved rapidly into development teams pushing off quality responsibilities, and the reinvention of sign-off theatre. The risk backlog can be thought of as an extension to the entire team of the cross-cutting responsibilities of a test manager described by Katrina Clokie (and others).

Organization

In the organization we worked in, the Platform QA team was a peer to four-and-a-half other software development teams in a department of around 50 people, reporting to a single technology departmental head, and distributed across five locations across Asia. The Platform QA team was the smallest of the teams, at 2-4 people, and were all in the main development centre.

A small tools team (the half a team above) of 1-2 developers was dedicated to work on tools and worked closely with the QA team. They partnered closely with, but were not merged fully into, the Platform QA team during the time period described, due to reasons of location, differing skillset and broader organizational concerns; though at time of writing such a merge seemed a sensible evolution. QA team members had either a manual testing background where they had gone on to learn scripting, automation and programming skills, or were graduate developers brought directly into the team.

Development teams were organized on “extended component team” lines. They owned a number of functionally related components, which they worked on together according to product need. Developers would contribute to shared libraries and tools, but rarely contribute to components owned by other teams, even when within the same trading platform.

One product owner set priorities for all development teams, using either a common product backlog of epics, or a more fine grained team-specific backlog of individual tasks.

Overall the department structure was influenced by Large Scale Scrum, but was not a site of a full LeSS implementation (as these variations from the LeSS playbook show).

Platform Maturity and Automation

An important constraint and enabler of Platform QA for us was the technical character of the platform itself. The high-performance, low-latency trading platform was a highly successful one that had been developed over a period of around fifteen years. The platform was built in-house, using a mix of different programming languages and underlying technologies, and formed a distributed system of 20-30 components. Production and QA environments had hundreds of deployed instances of these components.

At the time the Platform QA team was formed, the bulk of the platform had respectable coverage by automated tests, with a mix of unit tests and component-level functional tests. Up to date results of these tests were provided by continuous build infrastructure. Getting a one character patch into source control, through a build, and into a QA environment, with tests run, had a lag of a few hours. Functional tests also ran automatically overnight.

Functional tests were mostly written in a Behaviour Driven Development (BDD) style using the open source Robot Framework. Though usually described as an Acceptance Test Driven Development (ATDD) framework, we found it easy and powerful to work with its BDD features, simple to extend in Python and Java, and slightly superior to BDD-only competitors. For example, Robot has always automatically exposed methods from a library as BDD directives by translating camelCase() format to a directive named “Camel Case”, without any additional boilerplate.

This same functional test tooling was also employed to write end to end (E2E) automated test cases spanning multiple critical components. These were useful for demonstrating the behaviour of the overall product and the continuing integrity of the platform, given the underlying component builds changed frequently. There were hundreds of E2E tests, an order of magnitude less than other tests. These tests were higher maintenance due to the complexity of multiple component interaction, but we found this cost worth paying to maintain confidence in independent releases by the autonomous development teams. The owner of the end to end tests was the Platform QA team. BDD is a mesh technology for co-ordinating human and system aspects of a product. Having end to end tests in business facing language reinforces the common product definition, and system-wide thinking, that both Platform QA and the overall software process promotes.

Changes to the E2E tests came mostly from development teams, as automated passing of E2E tests served the same role as traditional QA sign off.

An internal web site showing the state of environments, test statuses (in summary), and releases was an important supplement to standard continuous build infrastructure. We think of this website, combined with continuous build, as a Health Dashboard. This was used by all development teams to navigate environments, releases and tests.

Software development organization maturity is not a simple linear progression, but a certain amount of automated test coverage seems necessary for a Platform QA structure to work. When reliable automated testing is not in place, the highest quality risks for the organization are usually improving automated coverage at a component level, which is more efficiently done by teams working independently than with a shared QA horizontal.

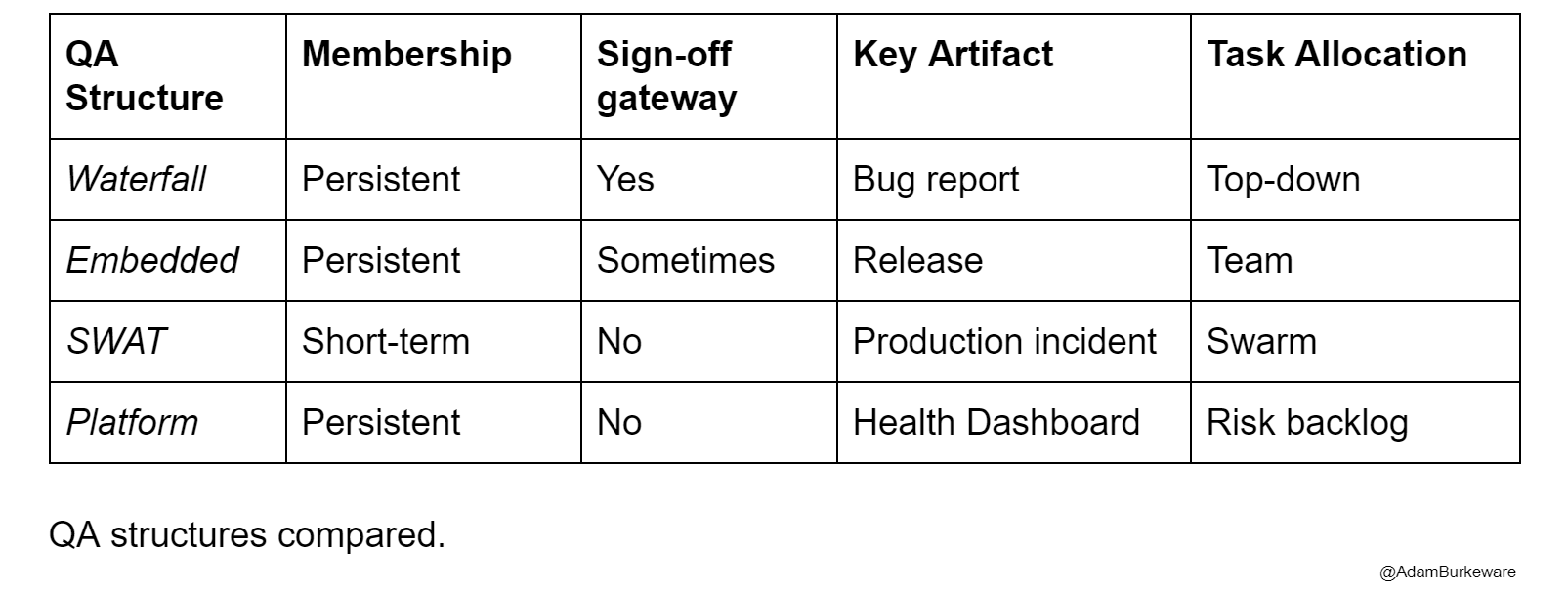

Types of QA Contrasted

The work of the QA team is intimately connected to the software process followed by the organization, whether explicit or implicit. One way to understand what we mean by Platform QA is to compare it to other forms of QA structure and process.

Waterfall

A dedicated QA team tests software delivered by a separate development team or teams after an extended development cycle of several weeks or more. They identify defects and go through a cycle of patching and retest with that team and component. They act as a final gatekeeper that signs off a particular component for release into other environments, including production. Automation is limited or post-hoc. QA team members are assigned to tasks by a QA lead or business prioritization process. Resource scheduling and prioritization is a key skill.

Embedded QA

Testing specialists sit entirely within development teams, and share responsibility for team deliveries. Teams stay together for extended periods of time (> 1 year). Prioritization is development prioritization with product owners. The intention is for skills and responsibilities of all team members to become more fungible over time (eg testers code and developers test more according to need). This structure is common advice when transitioning teams to more agile ways of working and often useful. Failure modes can include localized waterfall, and problems arising in shared behaviour or artifacts across teams (tragedy of the commons).

SWAT QA

This is a dynamic, short-lived team organized around a quality crisis, with the term due to Torok Gabor.

Team members are drawn from across the organization and mostly self-selected based on their passion to make things better. This can be very useful and was one inspiration for us in rethinking our team structure - in fact for a time we described our team as SWAT QA. A key difference with Platform QA is duration. SWAT QA is a short term team organized around resolving a particular crisis, rather than a persistent team addressing longer term quality risks.

Platform QA

Platform QA are a persistent team who focus on the quality of the platform, not single deliveries or components. They are partners to agile development teams who take responsibility for their own deliveries, including signing off and proving the overall integrity of the product (including playing well with other components). Platform QA teams work to a backlog of identified quality risks. This can include embedded engagements of a few months partnering with particular development teams to remediate these risks. They are also the ultimate owner of artifacts proving the integrity of the entire platform, particularly end to end tests.

The particular history of our department was: starting with a waterfall QA team and little or unreliable test automation (~7 years), splitting the team to run as individual embedded QA within development teams while building out automation (~3 years), then running as a horizontal platform QA team to improve the coherence of the platform and address the most relevant quality risks (~3 years).

The QA Metro

Somewhat speculatively, note that a parallel team, that has a close hand in tools, and collaborates with multiple teams to improve their process and systems, also has a lot in common with a good software architect. We have in mind the hands-on, collaborative enabler described by, say, Gregor Hohpe, rather than an older fashioned waterfall architect that handed down a design document and walked away.

There was no full-time architect in our department, but it was a title I used, for example, when explaining why I was chairing a consultative design review. Hohpe uses an image of riding the Architect Elevator to connect the realities of the technical infrastructure to the concerns of executive management. Perhaps we can think of riding the QA Metro, touring the platform, tightening loose bolts and noticing mysterious puddles of oil that don’t make sense. Incorporating those details into a systemic picture that makes sense of the health of the platform shows where the architecture is succeeding, where it is stressed, and how it may need to evolve.

The ideas of shared responsibility from DevOps, and operability from Site Reliability Engineering (SRE), were also practices we tried to draw on, and some part of the culture of the broader team. Another way to conceptualize Platform QA might even be as “Quality Reliability Engineering”. Dev, QA and tools groups had a constructive, long-term relationship with the knowledgeable production support team dedicated to the platform, though day to day interactions between dev and support were more frequent than QA/support interactions. There was also a degree of shared tooling and mutual patches across the groups. Characteristic DevOps disciplines, such as developers doing production releases, were however not part of the highly controlled bank production process. One speculative future evolution of a Platform QA team could be merging with platform-aligned support to form a common Platform Reliability team. To be distinguished from SRE the mandate would seem to need to stretch back into development process as well, which may be excessive scope.

Alternative Processes, Endpoints, and Transitions

In describing a particular process, an inevitable question is: “Why not just use X?” - where X is some other solution, in this context perhaps LeSS, feature teams, extreme postmodern testing, SRE, mob programming, or some other admirable technique.

Changing organizational structure is a political act, and politics is the art of the possible. In discussions of software process, this is often both easily elided by advocates of a particular process, and obsessively focused on by those more conservative towards process change, or those seeing process change as not within their reach.

Though there are many things to admire in, say, LeSS, it simply wasn’t the overall process the department ran. The organization had a highly successful platform and product, and certainly shouldn’t have upended its entire way of working lightly. Senior management was generally quite supportive of process and tooling innovation, as our lightly sketched history has shown. Agile process means adaptation to particular circumstances, perhaps even to the point of #noframeworks (ie, no explicit software process framework). We are sharing our experience in part to encourage teams to experiment with process and team structure improvements in a bottom-up way, independent of, or anticipating, senior-management driven change.

We have found this team structure a stable and successful one. Whether it should be considered a transition to some other process is an open question. For now we would say it shares certain values with good scaled agile frameworks, such as being product-centric, focused on reducing friction rather than establishing hurdles, automation-promoting, and skeptical about over-specialization. We hope our experience is useful to others.

References

Bratton - The Stack - On Software and Sovereignty

Clokie - Test Manager In Agile

Gabor - Short-Lived Functional Teams Work aka the QA SWAT Team

Hohpe - The Architect Elevator

Klärck and Härkönen - Robot Framework

Vodde and Larman - Large Scale Scrum (LeSS)

This article was originally published on LinkedIn.